More than 120 Swiss cities and municipalities are now pursuing formal smart city initiatives, and public-sector digital and sustainability projects accounted for a rising share of local investment budgets in 2024, according to the Swiss Smart City Survey. This expansion marks a shift in Switzerland’s urban economy, where digital infrastructure, data governance and climate resilience tools are moving from pilot status into the core of municipal capital allocation and shaping a fast-scaling startup ecosystem linked to public demand.

Policy context and institutional anchoring

Smart city development in Switzerland has evolved within a distinctly institutional frame. Urban digitalisation is not driven by national mandates but by coordinated action across municipalities, cantons and federal programmes. This decentralised structure reflects Swiss federalism, yet it also creates incentives for cities to professionalise digital strategies in order to access funding, talent and inter-municipal cooperation. Over the past five years, smart city initiatives have increasingly been embedded in official urban strategies rather than treated as innovation add-ons.

Federal policy has reinforced this trend indirectly. Programmes supporting digital public services, climate mitigation and energy efficiency have created demand-side signals for technology adoption at the city level. Municipalities that align smart city projects with national climate targets or energy strategies can justify long-horizon investments while maintaining fiscal discipline. As a result, smart city activity has expanded beyond large metropolitan centres to mid-sized and smaller municipalities seeking operational efficiency and resilience.

Capital allocation and funding dynamics

The scaling of the smart city startup ecosystem is closely linked to how capital is allocated within public budgets. Municipal spending on digital infrastructure increasingly prioritises platforms, data layers and interoperable systems over bespoke applications. This favours startups offering modular solutions that integrate into existing urban systems rather than single-purpose technologies.

Public procurement remains the dominant revenue channel for many smart city startups, particularly in early stages. Contracts are typically smaller than those in national infrastructure projects but provide stable, multi-year demand. This procurement-driven market structure encourages incremental scaling and reduces revenue volatility, albeit at the cost of slower expansion compared with purely commercial markets.

Private capital has begun to complement public demand. Venture and growth investors show rising interest in urban technologies that address energy optimisation, mobility efficiency and environmental monitoring, especially where regulatory clarity and recurring municipal demand reduce market risk. The result is a hybrid funding model in which public capital absorbs early adoption risk while private investors support scaling once products demonstrate institutional fit.

Market behaviour and startup positioning

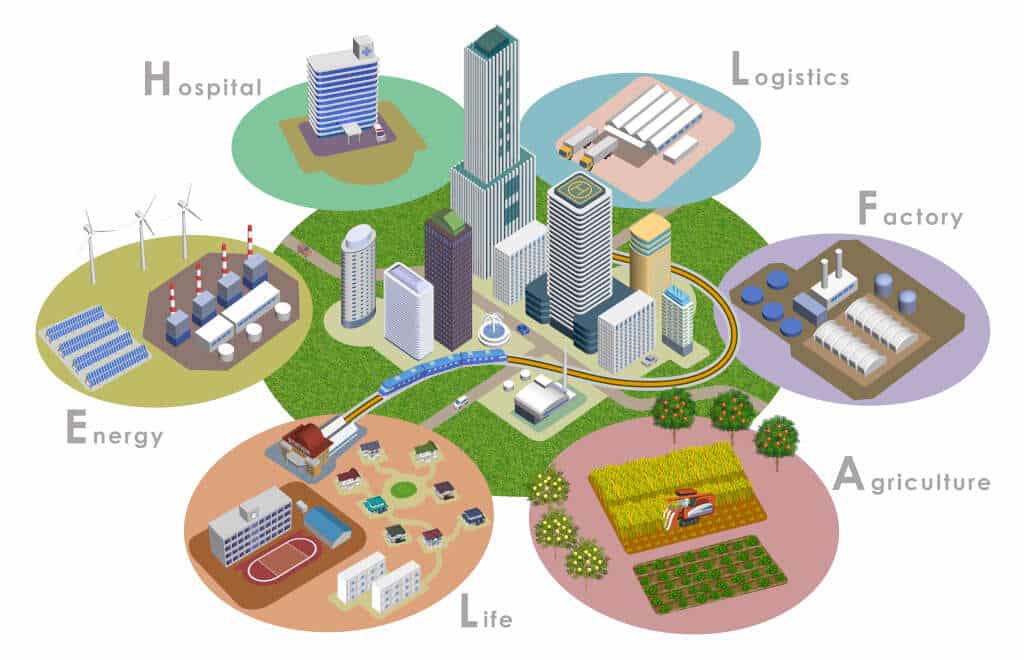

The Swiss smart city startup landscape is characterised by cross-sector positioning rather than vertical specialisation. Many firms operate at the intersection of data infrastructure, climate resilience and operational optimisation, allowing them to serve multiple municipal use cases. This flexibility is critical in a fragmented municipal market where city sizes, budgets and priorities vary widely.

Startups supplying IoT connectivity, data platforms or analytical tools benefit from economies of scope. A single deployment can support applications ranging from traffic management to energy monitoring or environmental sensing. This market behaviour favours technology providers that invest early in standards compliance, data security and interoperability, attributes increasingly demanded by public buyers.

Investor behaviour reflects this dynamic. Capital flows tend to favour companies with scalable architectures and the ability to aggregate demand across municipalities, rather than those reliant on bespoke city-by-city customisation. As smart city spending grows, concentration effects are becoming visible, with a smaller number of platforms capturing a disproportionate share of deployments.

Evidence from Swiss operating contexts

Operational evidence from Swiss municipalities illustrates how startup solutions are being absorbed into urban systems. Sensor networks and data platforms are increasingly used to inform decisions on energy use, traffic flows and environmental exposure. Rather than replacing existing processes, these tools typically augment administrative capacity, enabling cities to respond more quickly to changing conditions.

Data sovereignty has emerged as a key criterion. Municipalities show a preference for infrastructure that stores and processes data domestically and complies with Swiss and European data protection standards. This preference shapes procurement outcomes and creates competitive advantages for startups aligned with local legal and governance expectations.

Smart city projects also show spillover effects. Data collected for environmental monitoring can inform public health assessments, while mobility analytics support both transport planning and climate reporting. These complementarities increase the economic value of digital investments and strengthen the business case for continued deployment.

Governance, coordination and scaling constraints

Despite rapid expansion, governance remains a binding constraint on scaling. Municipal capacities differ significantly, and not all cities possess the expertise to manage complex digital systems. This creates uneven adoption rates and increases reliance on external partners, including startups and integrators.

Interoperability across municipal boundaries remains limited. While national and regional networks facilitate knowledge exchange, technical integration often lags behind policy coordination. Without shared standards and procurement frameworks, scaling remains resource-intensive for both cities and startups.

Risk management is another constraint. As cities collect larger volumes of data, concerns around cybersecurity, system resilience and vendor dependency intensify. Municipalities increasingly require demonstrable risk controls and long-term support commitments, raising entry barriers for younger firms but strengthening overall system robustness.

Trade-offs between innovation and inclusiveness

Smart city expansion introduces trade-offs that influence investment decisions. Digital services can improve efficiency but risk excluding residents with limited digital access or skills. Swiss cities have responded by emphasising user-centric design and parallel offline access, but this increases implementation costs and complexity.

Fiscal trade-offs are also present. Investments in digital infrastructure compete with spending on housing, transport and social services. The political acceptability of smart city spending depends on its ability to demonstrate tangible benefits within electoral cycles, reinforcing the focus on operational improvements rather than experimental technologies.

Forward implications for the ecosystem

The Swiss smart city startup ecosystem is entering a phase of consolidation and professionalisation. As more municipalities adopt formal strategies, demand for reliable, interoperable solutions will intensify. This is likely to favour companies with established track records and the capacity to support long-term public-sector partnerships.

From a policy perspective, the challenge lies in maintaining diversity and innovation while avoiding fragmentation. Shared standards, coordinated procurement and clearer data governance frameworks would lower scaling costs and broaden market access for smaller firms.

The evidence suggests that smart city development in Switzerland is becoming an integral part of urban economic management rather than a technological trend. Capital allocation, governance capacity and risk management now determine which innovations scale and which remain localised. As cities continue to invest under tightening fiscal and environmental constraints, the smart city ecosystem will increasingly be judged by its contribution to resilience, efficiency and institutional credibility rather than by the novelty of its technologies.

Referenzen (APA)

- Swiss Smart City Survey 2024. (2025). Swiss Smart City Survey. Available at: https://smartcity-survey.ch/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1_Final-Report_2024_final_EN.pdf

- Paradox Engineering company profile. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paradox_Engineering

- Scandit company profile. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scandit

- Sparrow Analytics smart environmental sensors. (2024). CleanTech Alps. Available at: https://www.cleantech-alps.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/AnOverviewOfCleantechStartUps.pdf

- Smart Cities vertical. (n.d.). Kickstart Innovation. Available at: https://www.kickstart-innovation.com/smart-cities-vertical

- Switzercloud IoT platform. (n.d.). Switzercloud. Available at: https://switzer.cloud/en/switzercloud